Skiptrace jam devlog (P2): plumbing to foundation

After a weekend relaxing (mostly playing Metroid Fusion and watching Code Geass R2) and thinking of ideas during the school week, it’s time to get this game planned and fleshed out. First stop is the game design doc!

Table of contents

Plumbing

While many are likely able to come up with a quick concept and get going, I try to be a planner, not a pantser as much as I can. Last time we were here, I laid out some ground rules on what I’d want to make and how I’d want to make it.

- I’m using PICO-8 for the engine. There’s a lot of good resources, I can get reacclimated with Lua, and it helps me keep scope down and make the most of the limited toolset I have since I know I’d try different features to make something extravagant and likely never finish. Also helps that it gives an opportunity for a great visual style as someone who can’t do pixel art: the Zelda Game Boy/Color games are definitely going to be big inspirations for the artstyle.

- Emphasize replayability to make the most out of limited time. An arcade-style score-attack approach or a sprawling search-action game are both good methods, but I’m thinking of going with a mixed approach to get the best out of both worlds.

- With a theme of “all eyes on me,” motifs of visibility and surveillance are a core part of the game’s identity. Originally, I had a few ideas of how to implement it in gameplay regarding the casting of light, but I think the 1984 “you are being watched” concept feels more interesting to commit to.

- Finally, and most importantly, I want to expand my horizons and do something I don’t have a lot of experience playing or thinking about, so I’m planning on a shmup/search-action combo for our genre.

Having these gestate over the weekend and with some inspiration from a certain Game Boy Advance game[1], I got a very basic idea on Skiptrace[2], the name I decided to go with since it fits perfectly with the surveillance motif. But what good is just an idea if we can’t think about how it applies?

From Concept to Content

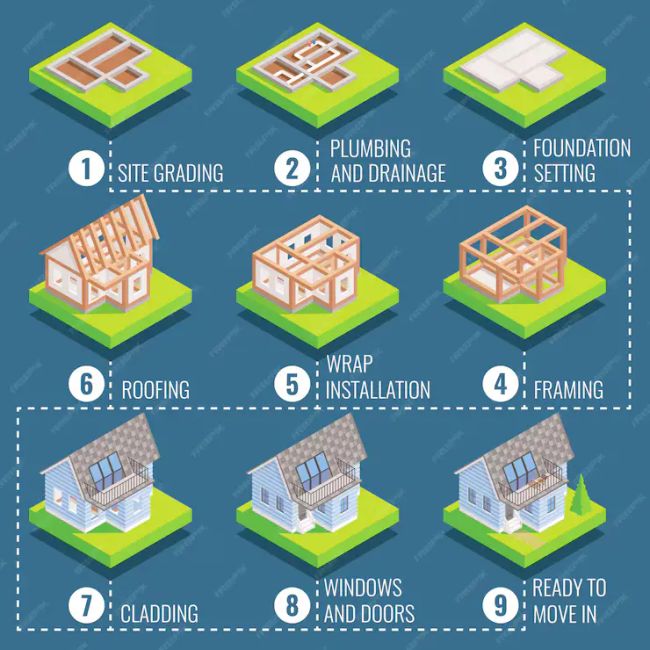

No game is rock solid without a sound design doc, as Starfield taught us, and while you don’t need a 500-page manifesto for a month-long game jam, it’s better to go in with a plan and strict guidelines for what you’d want to work on than come up with it on the spot as you go. It’s like building a house, except instead of crashing a market, you crash on your keyboard instead!

In this case, determining if you can even do the game jam in terms of schedule would be “site grading,” defining what you’re willing to work on is “plumbing,” and developing a solid concept is “setting the foundation.” If the site you’re building a house on is on unstable land, you probably shouldn’t build a house on it: it’s good to have aspirations to create stuff, but don’t throw your life into chaos by doing so, especially if it’s a project with a time limit.

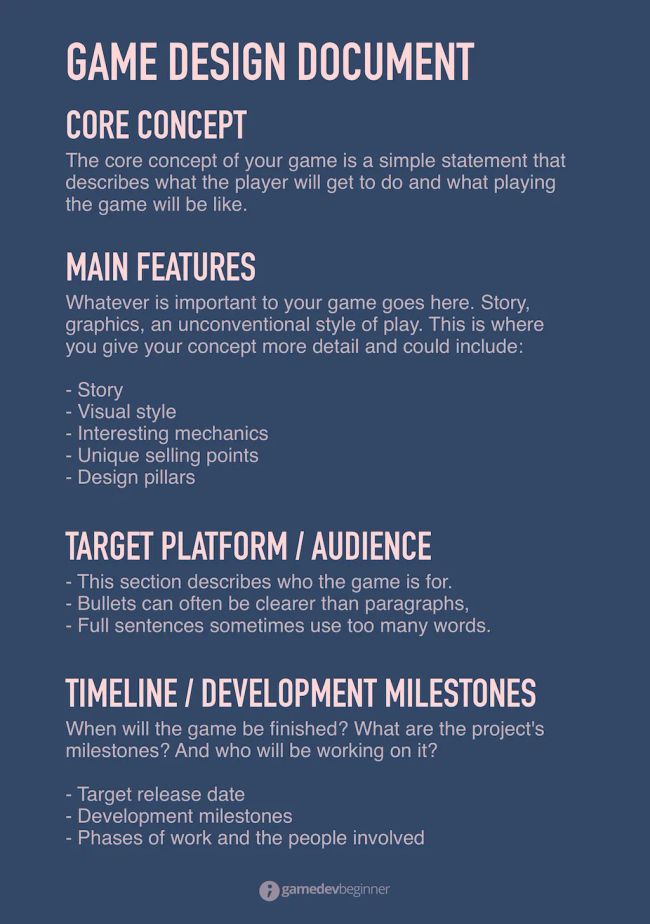

We can take that analogy of constructing a house into constructing a video game and writing down the plan for that is called a “game design document.” There’s a variety of resources and design docs that you can find and use for what fits how you work: I have a collection of them that I’ve collected over the years here. What works best for me is building a core “concept” doc: a limited 1-page outline of everything I want to work on that I then expand out more and more.

We can break this down into a few key areas:

- Core Concept Statement: what is the game that we want to make?

- Design Pillars: why do we play it?

- Mechanics and Controls: how do we play it?

- Target Audience: who is playing it?

- Story and Aesthetic/Audiovisual style: when and where is the game?

- Project Management (milestones, release platforms, etc): when and where are we playing it?

- Finally, a refined Core Concept Statement: what is the game that we’re actively making?

A core concept statement should be like a thesis for a research paper: it should reflect the core ideas of what you want your game to be. Generally, I make two of them, a concept statement based off the ideas that first come to mind, and then edit it after I finish the rest of the project.

Crafting a Concept Statement

A “concept statement” is basically the one-two sentence description you see of the game on Steam or a more enthusiastically written declarative Wikipedia sentence. This packs a lot of punch and is what would sell the game to people, so it’s important to keep it strong. We don’t have design pillars, mechanics and controls, a target audience, story, or style to go off of, so a concept statement is just based off the initial “plumbing” we have setup. Generally, for me, the basic format for a concept statement goes…

[Title] is a [artstyle] [perspective + genre] [story] featuring [adjective + design pillars x3].

…though you can move things around when you’d like. For Skiptrace at this part of development, my statement was:

[Title: Skiptrace] is a [Genre: 2D shmup search-action] game [story: exploring rebelling planet IRIS-372], featuring [design pillars: arcade-y combat, progressing exploration], and a [style: retro 8-bit style].

Design Pillars

These are the core objectives of your game and why the player is engaging with the game’s mechanics and systems. A trick I come up with is to tie an objective (say, in our case, exploration) to an adjective or feeling (”delve,” “probing,” “puzzling”): this helps me know what emotions I want the player to feel when they strive for the core objectives while also adding flavor to the concept statement.

Skiptrace’s design pillars are progression (”evolving”), combat (”twitch”), exploration (”probing,” “delving”), and style (”ritzy,” “retro”).

Mechanics and Controls

I expand from the design pillars to build out how those pillars are implemented within gameplay. An example of a fully-expanded mechanics/implementation outline for the progression pillar is below.

Example Design Pillar: “Evolving” Progression

- I want level design that “spirals” deeper into the planet’s core. Since I only have a limited amount of time, I thought of a “marble” planet for the map where there are 4 different quadrants that the player can use the bands/empty space in between to travel before touching down.

- I want the player to return to past areas with new abilities for general upgrades and pickups.

- As the ship feels more capable, increase the number of enemies in the atmosphere.

- Have bosses in the atmosphere that the player can rise from within the quadrants to fight.

- 4 pickups, 2 variants, and 1-2 upgrades/area, though this could always be scaled down.

- I want the player to feel like they are “evolving” and “strengthening.”

Target Audience

For a released game, this matters a lot more: every game has a purpose and you should know the types of players who will understand and resonate with that purpose the most. Since this is a game jam, I don’t have to spend as much time thinking about a target audience since anything can be submitted, but I’ll say my target audience are genre-fans (those who are already fans of shmups and search-action games) or those who enjoy challenging content that’s perfectible and has high replay value.

Story and Audiovisual Style

The main narrative of Skiptrace is where I insert the motifs relevant to the jam theme of “all eyes on me” in their clearest form. Not all games need fantastic writing or voice acting, but the belief that game’s don’t necessitate a story isn’t entirely true either. The core of any game making an impression on the player is motivation and while the game being fun is the strongest motivation you can have as a developer, how do you appeal to someone who doesn’t already enjoy the game or have the game resonate with the player when they complete it? Story and style accomplish this best, so even if it’s not grandiose, having a concrete and consistent narrative motivation for the character and thus the player to participate is essential.

In our case, Skiptrace is about our heroine Rei Onnant, pilot of the Thrush as she becomes IRIS-372’s last hope standing against RETINA Corporation, implants their empire or surveillance and inhumane efficiency across the entire Solo galaxy. Generally, I like to write core plot points as well as the general motifs featured within the narrative and how the narrative connects to the gameplay. This keeps the game consistent from top-to-bottom regarding a united motivation for the player to pursue their goals in both gameplay and story.

In terms of audio/visual style (aka aesthetic, artstyle + music/sound, etc), PICO-8 is excitingly limiting. I know my vision and believe that if I was using a more capable engine like Godot, I would unfortunately worry a bit too much about artstyle. Sometimes restrictions on scope and capability breed creativity, and PICO-8s 32 color palette and small, but deep toolset gives me some ideas on how to approach aesthetic as someone with limited music composition background and virtually no drawn artistic experience.

For Skiptrace, the main influences in terms of artstyle are the Zelda Game Boy games, especially in their use of color, and Evangelion for bold text and eclectic visuals. I’m planning to go for an atmospheric soundtrack that builds as the player makes progress within the level: definitely influenced from the art I’ve been tapping into as of late (Boat’s Let’s Start Here, Metroid Fusion and Celeste’s soundtrack to name them), but it fits the vibe I want to give off with this game.

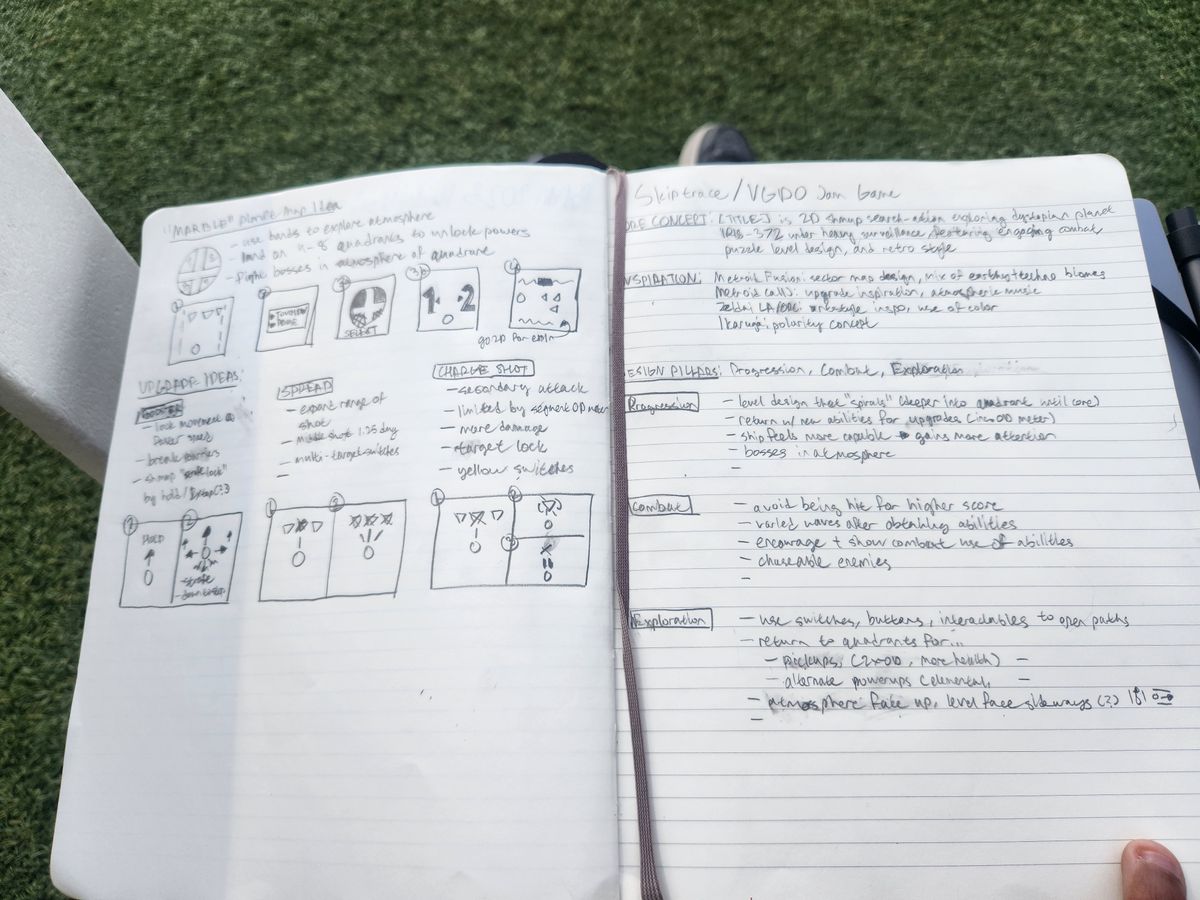

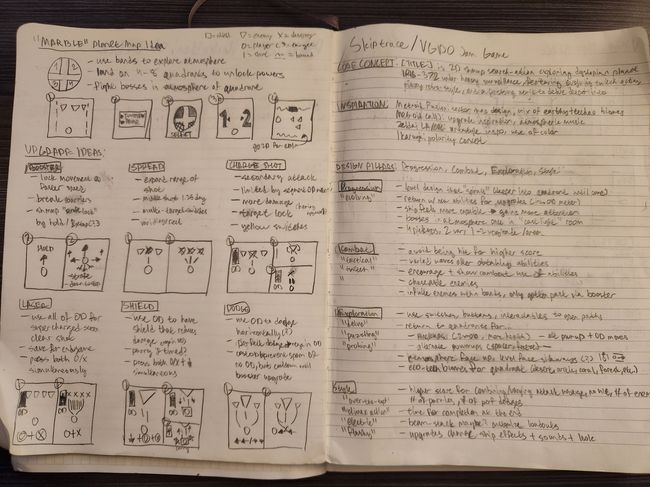

Project Management

I only have a month (now three weeks) to complete this game for the jam, so project management is going to be essential. I’ve been keeping design elements and ideas within my game dev notebook and transferring them to Notion where it’s relevant to organize. Given that spring break is up soon, that’s probably going to be an important period to make progress on this game: now that I have a solid idea of how I want to implement mechanics and style into the game, this weekend, I’ll be looking up learning PICO-8 and lay the groundwork for developing. A basic milestone layout for my purposes would look like:

| Milestone | Time spent |

|---|---|

| Learn PICO-8 menus and usage | 2 days |

| Draw level design | 3 days |

| Implement basic sprites | 3 days |

| Implement core movement | 2 days |

| Implement upgrades | 2 days |

| Implement transport between sector “levels” and atmosphere “overworld” | 1 day |

| Implement sound effects and menus | 1 day |

| Implement music | 3 days |

| Refinement | 5 days |

Refined Core Statement

Now that I have all of that information gathered, I can craft our refined, evocative core statement that reflects our design pillars, the mechanics that our players use to reflect them, and the emotions our players resonate with.

Skiptrace is a 2D shmup search-action game following heroine Rei of rebel planet IRIS-372, the last to fall to surveillance by the dystopian RETINA Corporation. With evolving twitch action, ritzy retro style, a probing world to delve deeper into, and all hopes and eyes on our pilot, will she overcome and perfect?

This is a decent core statement in my eyes! The game has an identity, the player reading it for the first time knows the general plot motivation and what the game will be like, and emotive design pillars communicate how players should feel playing Skiptrace based off the experience I’m crafting.

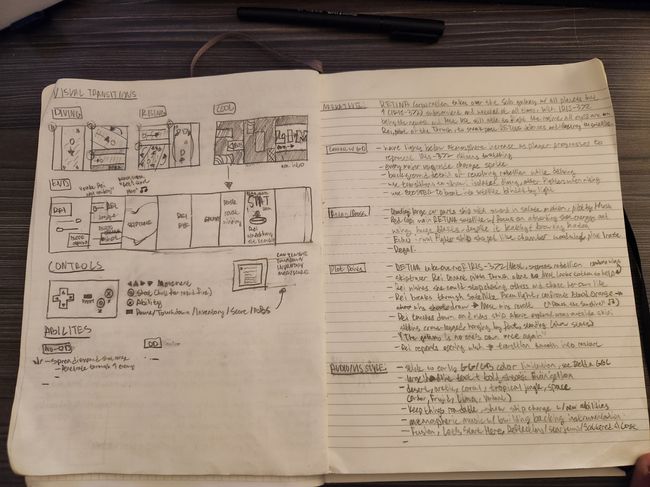

Drawing a Blueprint

Finally, while we can easily expand this text outline to be as large or as compact of a game design doc as we’d like, sometimes, things don’t express as well in text as they may do drawn. As a visual learner, drawing diagrams, annotations, crude drawings, or some form of visual companion to our text. The mixed blank/ruled paper notebook I use for game design and development (finally getting use out of it, hooray) helps a lot with this. Drawings and written explanations are side by side, providing important context and substance to my ideas.

To reiterate, the core to any creative process or personal progress is finding a system that works for you. It should feel natural and logical to lay out how you work: that’s how you do it consistently and how you do it well. For me, as a visual learner who tends to work best with a basic outline that expands outwards, one-page design documents that I add more and more to side-by-side with drawings to explain how mechanics or menus work makes the most sense!

What next?

Next time I update, I’ll have at least something to show in PICO-8 now that I have this mostly fleshed out. I still got to transfer from paper to Notion, but I have a very strong idea of how Skiptrace will play and progress. This has been fun to think about and draw up and I’m glad I get to make a game while you lovely folks get to read about it!

Until then, see you next post!

Last edited on .